If you think about it, most American sports involve an animal hide. Baseballs, basketballs and footballs are all made with leather. In Afghanistan, they don’t just use the skin — the game ball is a whole goat. Minus the head and hooves.

Buzkashi, which translates into something like ‘goat grabbing’, is the national game of Afghanistan. And, as the name suggests: the object of the game is to grab the headless, disembowelled goat or calf carcass,circle the field and deliver it to the goal.

Simply put, it can be described as “polo with a headless goat,” the comparison doesn’t really hold up. The rules vary by country, but most buzkashi matches have no teams, no clock, and no clearly defined playing field.

It originated among the Turkic people of Central Asia centuries ago, and for generations, they’ve been passing down the game, and the goat, relatively unchanged. It’s more than a game; it’s a part of the fabric of Afghan life. And its popularity has never waned.

It’s a war of all against all, in which the winner is the horseman (traditionally, only men play the game) who successfully carries the carcass past some defined point or throws it in a certain area.

In the northern Afghan city of Sheberghan, you can catch a game after Zuhr prayers most Fridays in the winter. That’s buzkashi season.

Afghan refugee expresses his love for Buzkashi and hopes for his community

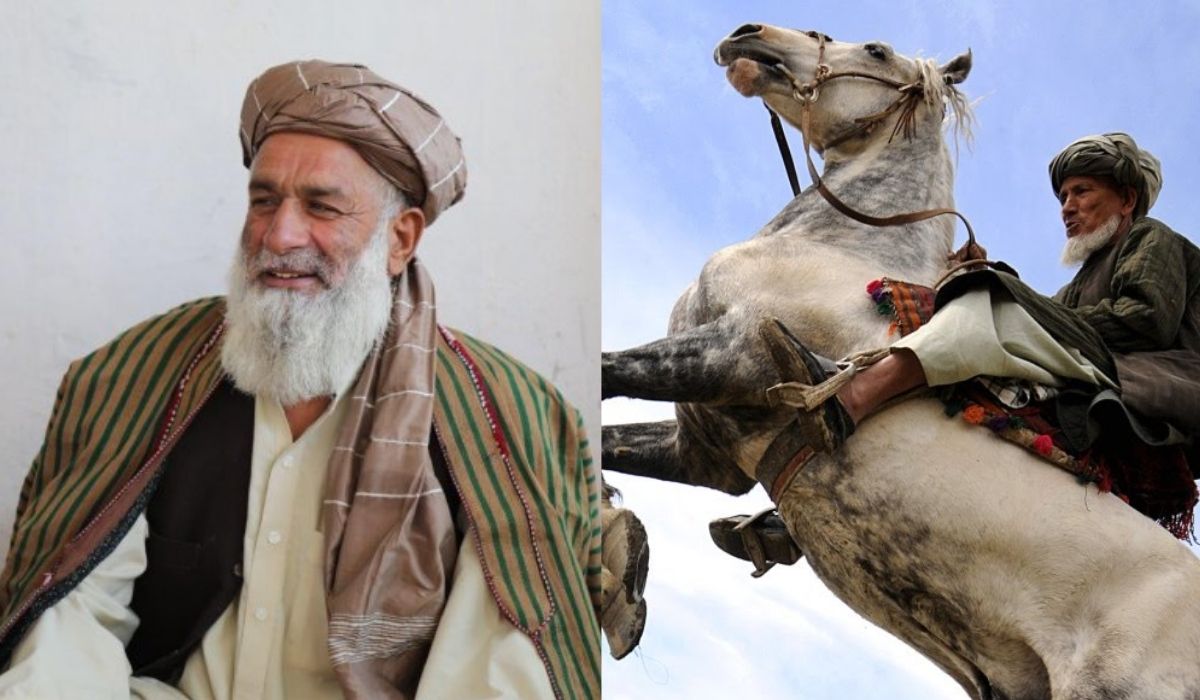

Haji Gada Muhammad is an elderly Afghan refugee living in Pakistan whose love for Buzkashi helped him connect with his new community in Pakistan after he fled Afghanistan during the Soviet invasion.

In a recent interview with UNCHR Pakistan, Gada Muhammad explains the allure of the traditional sport of buzkashi and expresses his hopes for young refugees.

Now over 60 years old, he still retains fresh memories of the Afghanistan he fled over 40 years ago, as if it were yesterday.

Haji Gada Muhammad sits on a cushion in a splendid white Peran o Tunban (a traditional Afghan dress for men). A grey turban is wrapped around his head, perfectly modelled from years of practice in wearing the nearly six yards of silk.

“I remember how it looked when I left,” he recalls. “I can see the green pasture in Kunduz and Badakhshan that I was familiar with. I can remember feeling lost and not knowing when the ordeal of conflict would end, or if I’d be able to take my herd back into the valley near my home again, sing, be free from fear.”

Though he enjoys the peace and comfort of living in Pakistan, he is worried about his besieged brethren in Afghanistan. Baba Gada Muhammad says he is saddened that Afghans still continue to struggle for restoring peace and security in their homeland.

“I can only raise my old hands in supplication and pray for the restoration of peace and prosperity in my country. I want to be able to re-live the happy moments of tranquillity I knew in my childhood.”

Bringing the Pashtun community together through sport

Gada Muhammad believes that sport got him through a lot in his life and helped him build better social connections with the host community herein Pakistan. “The people of Pakistan had open hearts and warmly took us in,” he recalls.

Being far from home, he wanted to keep his culture and identity alive. It was through the sport of buzkashi – his country’s national sport – that he was able to do this.

Haji Gada Muhammad describes the buzkashi as a test of speed, strength and horsemanship.

“It’s not just a tug-of-war among horsemen over a sewn-up goat carcass. It’s the skill, strength, speed, cunningness of the horseman that wins. It’s rooted in a more traditional way of life in the part of Afghanistan I come from.”

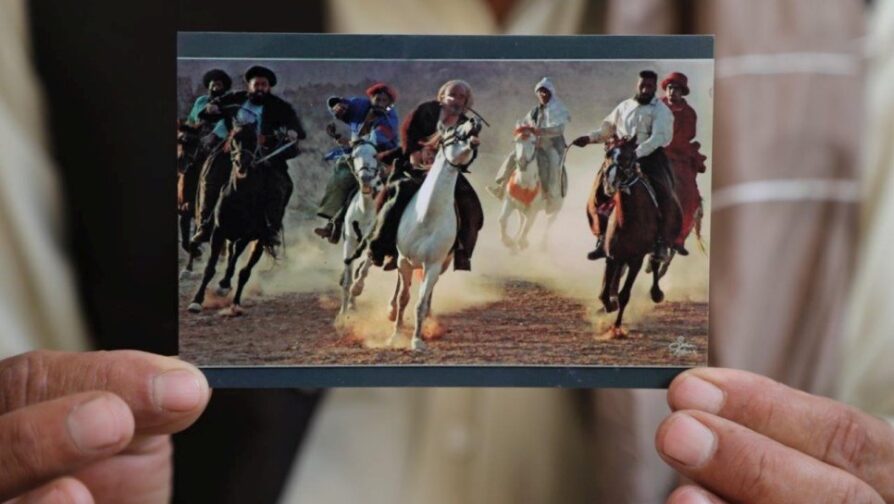

Spurred on by Haji Gada Muhammads’s enthusiasm for buzkashi, the people of Quetta also picked up the sport, formed their own teams and participated in many tournaments over the years.

Due to his love and dedication to the sport, he has been invited to hold buzkashi exhibitions at many popular festivals in Pakistan. Today, many medals and shields of appreciation sit together proudly with photographs of tournaments on a table in Haji Gada Muhammad’s house.

Age has not diminished his love of sport; even today — at the age of 60 — he continues to organize and participate in Bazkashi tournaments every. He also organizes Afghan wrestling tournaments sometimes on Fridays.

Unfortunately, his sporting activities have been halted temporarily due to the COVID-19 situation.

Haji Gada Muhammad wants buzkashi to become an Olympic sport, though acknowledges that “there might have to be some changes, like using a sack instead of the traditional goat.”

Hope for the future of Afghanistan’s youth

Haji Gada Muhammad has great faith in the young generation of Afghanistan, given their potential to change the destiny of their nation. He uses sports to play his part in supporting them and making them aware of their values and strength.

Most of the riders and wrestlers that take part in the tournaments he organizes are young men. He is proud that he could contribute to uniting the locals and refugees through his sports events.

For Haji Gada Muhammad, sports are important not only to tie communities together but also as a lifeline for youth and a way to keep them from harmful activities.

As a mashar (elder) of the Afghan community, he is hopeful about the future of the upcoming Afghan generation.

“They have immense potential and can bring peace and prosperity to the country eventually,” he says. Afghanistan has one of the youngest populations globally, with 47% under the age of 15.

“Education is important for this generation of Afghans… I understand the pressures that young people are under. I can only urge them to do their best to obtain an education and to develop their skills and capacities. My advice: be law-abiding and remember your roots. One day we will be needed to rebuild our country.”

Erwin Policar, a representative of UNHCR’s in Quetta, said that believes Haji Muhammad Gada has reason to hope for a better tomorrow for Afghan youth.

“Nowadays, we see Afghan children attending Pakistani schools and receiving the same education. Accredited education is important, and we’re hopeful that more opportunities will be available to young Afghans as they progress with their education.”

In the end, Haji Gada Muhammad said he can’t wait to resume his sporting activities once the pandemic is over. He plans to get the COVID-19 vaccine, which Pakistan is making available to Afghan refugees.

When asked if he’ll be watching the Olympics, he said “of course.”

When we ask which sport, he smiled and replied: “Will they have buzkashi?”