“Rome and Sparta for many centuries stood armed and free”, wrote Niccolo Machiavelli in ‘The Prince’ in 1513. The Pashtuns too, have stood very armed and very free along the mountainous Pak-Afghan border in an area that has become known as the ‘graveyard of empires’.

A people reputed to be either ‘your best friend or your worst enemy’ they have been armed to the teeth since the first bow was strung, resisting conquest by imperial powers for more than 2,000 years. Alexander the Great nearly lost his life in the 4th Century B.C, while confronting them in what is now the Malakand District. Genghis Khan failed here. The Mughal empire too failed to subdue them or extract taxes from them for three centuries. It was the Pashtuns led by Ahmad Shah Durrani who inflicted the defeat on the Marathas at the battle of Panipat, it was the Pashtuns who wiped out an entire British army of 18,000+ soldiers sparing none but one man — Dr William Bryon, so he could go back and warn his government not to approach them with imperial motives again. It was once again the Hotaki Pashtuns who seized control of Persia from the Safavids. The Soviet Union suffered outright defeat in their lands sending it into eventual collapse. In 2001, the Western coalition led by the United States invaded Afghanistan. The Coalition forces have spent more than 1 Trillion USD in the war and lost 3,502 soldiers during combat while more than 60,000 US veterans of the war committed suicide during the period 2012 to 2020 alone. The result — after 2 decades, it has failed to crush the Pashtun dominated, hard-line, conservative Afghan Taliban movement and agreed to withdraw from Afghanistan through a peace deal signed in Doha on February 29, 2020.

One wonders what causes these highland clans, divorced from modern technology to defeat sophisticated super powers even in the 21st century. The answer is rooted in the economic foundations of the Pashtun society which shaped its social structures in such a way that they breed the fiercest armed resistance anywhere in the world.

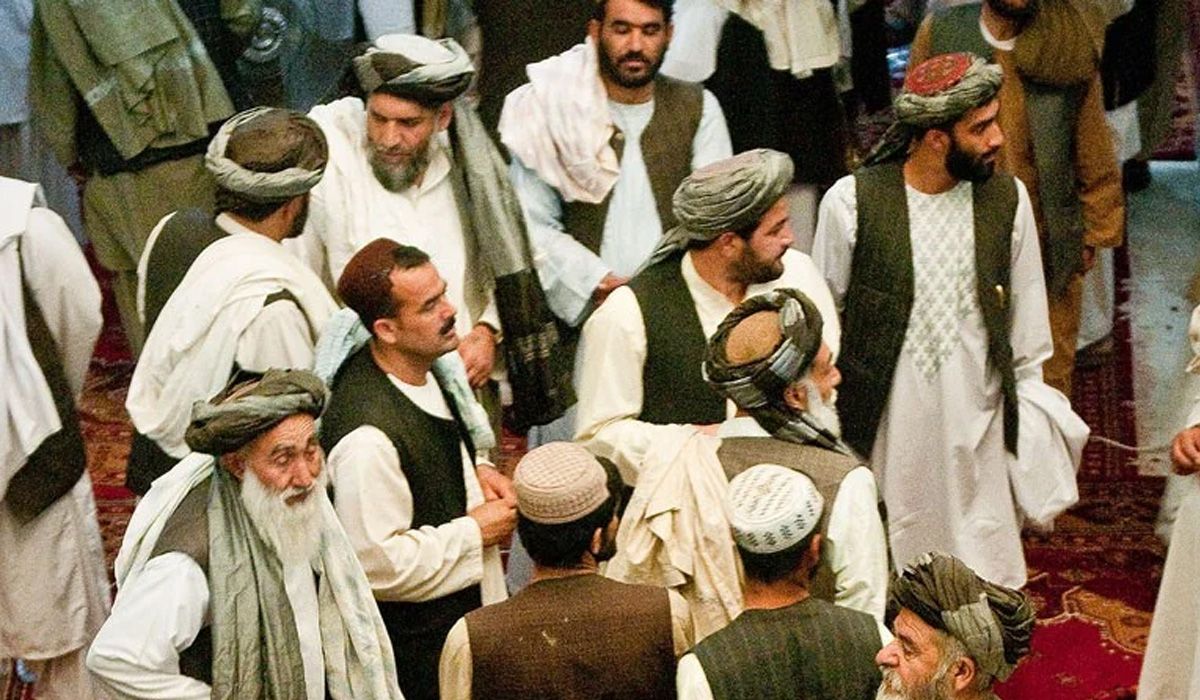

Ibn Khaldun, the 14th century historian, sociologist and economist was one of the most ardent advocates of the theory that a person’s or group’s outlook on life owes the way it is to how livelihood is earned. The vast majority of Pashtuns live by a clan based economy similar to other highlanders, the Chechen & Dagestani Muslims of the north Caucasus and the Scots till the 18th century. The need for a clan economy is best emphasised by the Chechen proverb which equally applies to the Pashtuns’ far more rugged landscape, “When will blood cease to flow in the mountains? When sugarcane grows in snow”. The scarcity of resources breeds harsh competition. As Sir Winston Churchill observed about them, “every tribesman has a blood feud, every man’s hand is against the other..”. Hence, the only way to keep your safety is to make sure you stick together in tribal clans. Clans only survive when the ‘group feeling’ is strong and that is always ensured through a defined code of conduct expected of every member of the tribe. For the Pashtuns, this is the ‘Pashtunwali’. The Pashtunwali ensures that a system of justice is in place to regulate the behaviour of the person as well as the clans. It sets out twelve principles; hospitality, asylum, vendetta, bravery, loyalty, respect for the environment, faith in Islam, pride, protection of women, honour of the weak, chivalry & homeland. Over centuries, these principles initially adopted to foster clan unity would enable them to become fierce warriors.

It would have a tremendous influence on developing their cultural memory especially those of the Wazir, Mehsud & Ahmadzai clans residing on both side of the Durand line where the resistance has always been strongest and a place former US president Barack Obama called ‘most dangerous place in the world’ with regards to implementing America’s foreign policy. It enabled a culture of strict egalitarianism and collective security to be established. It was the idea of ‘collective security’ originating out of Pashtunwali which ensured Pakistani Pashtuns pressured their government to covertly side with the Pashtun dominated Taliban against the Northen Alliance in the 90s civil war even if they disagreed with the Taliban ideology. Under the Pashtunwali, there was to be no landed aristocracy and therefore no peasant class. Every man be it a tribal leader or another, shared the same responsibilities unlike the ethnicities on the east of the river Indus where the influence of the Hindu caste system had ensured different functions for different castes. This enabled Pashtuns to mobilise all able-bodied men of age for war in packs of ‘lashkars’ whenever the need arise be it against another Pashtun clan or foreigners just as they easily continued to do so from various parts of Pakistan and Afghanistan post the American led invasion. When at peace with one another historically, they were launching united raids into India or Persia to loot riches and or build empires often for themselves under the likes of Sher Shah Suri and Ahmad Shah Abdali or as hired foot soldiers for the Mughals and other Islamic Turkic dynasties. Thus, a continued state of warfare embedded into them a martial lifestyle which was complemented by Winston Churchill in the words, “To the ferocity of the Zulu (South African warrior tribe) are added the craft of the redskin (native Americans) and the marksmanship of the Boer (European conquerors of South Africa)”. Such a clan economy also facilitated the way for mullahs or religious preachers to gain unchallenged soft power, something exploited by the Taliban for their rise. Since each Pashtun individual, clan or tribe considered him or itself superior to the rest, the only way to get them to come to any settlement had to be with the help of mullahs who interpreted and enforce judgements backed by divine texts which were held to be the only legitimate interventions since God was above all Pashtuns. This is why ‘calls for service to Islam’ or ‘holy wars’ in its name have easily appealed to most Pashtuns but not their immediate neighbours like the Punjabis who have never been able to put up a sustained armed resistance against an outsider.

Another major effect of the clan economy dependant Pashtunwali which has ensured their success in battle has been its designation of the duties of a woman. Like the Chechen and Dagestani highlanders, the Pashtuns emphasize on the need for many descendants. While the former boast the highest fertility rates in the Russian Federation, the latter do so in Afghanistan and Pakistan. The Afridi Pashtuns have a saying, “Blessed is he who has many sons and many guns”. This is because a clan is as strong as the power it can exert which is also directly proportionate to numbers. The norms imposed by the clan economy dependant Pashtunwali created a culture even in the early 21st century where marriage was the only career available for women like their 19th century British counterparts and numerically larger families were socially rewarded. The very high fertility rates enabled an excess youth bulge of sturdily built, well armed frontier men who could sustain huge losses of man power easily against foes like NATO.

Thus, America and its allies found themselves trapped in a fight with a naturally battle hardened and extremely passionate people who were able to mobilise their large youth bulge for war relatively quickly, whose vendetta code ensured that no casualty went unavenged, in a culture which promised the dead soldier with paradise and that too in one of the most rugged and remote landscapes in the world. No wonder when an ex soviet commander was asked as to what advice he would give to Americans fighting the Pashtun dominated Taliban, he said, “Leave at the first opportunity!”

Hence, in order to defeat the Pashtuns, one first has to remove their dependency from the clan based egalitarian economy. The religious zeal played a major role too, but we know how that has often failed when it is not backed by a co-operative socioeconomic structure. An evidence is of the various ‘Islamic holy wars’ launched against the British by Bengali Muslims in the 19th century the likes of the one led by Titumir which failed due to the clash within their class based societies while those initiated by Pashtuns always had a very different outcome.

Will these socioeconomic structures endure? It’s dubious looking at the Pakistani side where higher education is now very popular among Pashtun girls and boys resulting in late marriages and lower birth rates. Most are expected by their parents to opt for the field of medicine, a highly lucrative profession in Pakistan. Such new professions bring in a lot of money which liberates the individual Pashtun of the economic dependence on the clan and sometimes, even that of the wife from her husband. This weakens the hold of the Pashtunwali and all the norms associated with it. A Pashtun lawyer need not be a good marksman, display physical courage, be extremely hospitable or be a man of his word in order to be a good lawyer and hence those values die out. Such Pashtuns would only rarely take up fighting since its not rewarded in their daily lives. Though in Pakistan, the Pashtunwali still retains its influence in the rural areas of upper Dir or FATA, it has retreated from practical life in urbanised areas. One only needs to travel to Mardan to witness the rise of divorce cases initiated by women which was unthinkable at this scale only a few years ago. Pashtun youth readily absorb more modern English literature and therefore, the social norms of the English speaking world these days due to an increasing fluency in the language. Though this is a minority only, it is a significant one which possesses the potential to deconstruct and ideologically redirect Pashtun society towards accepting a more pacifist world view just as Japan and Germany did post the second world war.